Bad Museology

by Chris Littlewood

Published in Giovanna Petrocchi, Sculptural Entities

A Corner With Editions, 2021

Other text by Sunil Shah

Design by Sara Cristina Moser

Edited by Trine Stephensen

![GIOVANNA PETROCCHI, SCULPTURAL ENTITIES]()

![GIOVANNA PETROCCHI, SCULPTURAL ENTITIES]()

![GIOVANNA PETROCCHI, SCULPTURAL ENTITIES]()

![GIOVANNA PETROCCHI, SCULPTURAL ENTITIES]()

![GIOVANNA PETROCCHI, SCULPTURAL ENTITIES]()

![GIOVANNA PETROCCHI, SCULPTURAL ENTITIES]()

![GIOVANNA PETROCCHI, SCULPTURAL ENTITIES]()

One evening in September 2018, Brazil’s Museu Nacional in Rio de Janeiro was eviscerated by fire. As Latin America’s largest museum, its collection included some 20 million scientifically and culturally invaluable artefacts. Among those were dinosaur skeletons, a Pompeian fresco and the skull of Luzia – the oldest known human from Latin America. Devastated, as many Brazilians were by such a loss to their cultural heritage, the artist Vik Muniz was compelled to respond. Working alongside the scientists who were recovering what little remained, Muniz offered his capabilities in an attempt to retrieve some form of lasting connection to that history. Known for his ambitious photographic works that recreate popular imagery through complex collages, he was well placed for such an undertaking. By salvaging ash from precise locations in the wreckage, Muniz recomposed images of selected artefacts with material from their own remnants. Museum of Ashes, the resulting project, is a series of imitations either in photographic or 3-D printed form. Capturing some essence of the originals, they also highlight how visual artists can provide alternative possibilities in the face of scientific limitations.

“Scholars tend to ask only those questions that they can reasonably expect to answer,” says Yuval Noah Harari, author of Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. In describing early Homo sapien foragers, Harari points to a period, what he calls the curtain of silence, for which we have no concrete cultural knowledge. Only “a few fossilised bones and a handful of stone tools that remain mute under the most intense scholarly inquisitions.” Present-day tools can generate specific data like the DNA sequence of a mammoth tusk. But convey nothing about the meanings behind our prehistoric ancestors’ material expressions, such as the anthropomorphic animal engravings found on mammoth tusks. Many assume that the Paleolithic people who left those engravings – or those who drew the cave art at Serra da Capivara – had inherently the same minds of people today. Yet despite well-informed speculation, will we ever know what was behind their thinking? As Harari surmises, “these long millennia may well have witnessed wars and revolutions, ecstatic religious movements, profound philosophical theories, incomparable artistic masterpieces […] But these are all mere guesses. The curtain of silence is so thick that we cannot even be sure such things occurred – let alone describe them in detail.”1

Imperialism and the colonial impulse to acquire, map and collect has led to miscellaneous collections of artefacts and curios. Often housed in Western museums – not infrequently at the detriment of more vulnerable cultural groups – they represent, for some, an overwhelming history of inequality and destructive political ideology. And despite museums attempting to make their collections more widely available via open access public domains, the dilemmas of museology continue to run deep. What then is the role of contemporary artistic expressions in such a context? According to the artist Mark Dion “The job of the artist is to go against the grain of dominant culture, to challenge perception and convention.” Importantly for him, without destroying what was there before. Speaking about a group of like-minded artists, he says, “rather than dynamite the museum, our idea is to make the museum a better place, or more representative, more responsive, more enlightened, more interesting.”2 Unlike the sciences, that means asking questions without expectations; it means presenting highly subjective visual languages that not only challenge empirical theories. But also imagine potential new worlds – encoded with signs and symbols for future generations to decipher. After all, it was the human imagination that created ancient artefacts in the first place. In that spirit, we can picture the artist, not as an isolated genius but a link in the chain of cultural expression.

Archaeology and fragmentation are leading principles for creative people today. Identified by design curator Li Edelkoort as a predominant theme among young designers, her exhibition concept Post-Fossil brings together what she calls contemporary archaic forms. Excavating and recomposing, these design disciplines are rooted in a desire to hybridise earth-bound matter with technological advancements. By developing new material research in this fashion, Edelkoort argues that this generation of makers is fueled by their world existing in a time of disarray. Consequently, they are shifting the emphasis from a materialistic mentality – to one conscious of ecology and overconsumption. “They propose ritualistic tools for a new kind of well-being,” Edelkoort says. Likewise, established ateliers incorporate notions of archaeology into large-scale built projects, fragmentation into their research. Within what could almost be a movement, this propensity is also prevalent across the visual arts. Fittingly titled A Desire for Archaeology, Perspectives on the Future – an exhibition at Musée d’Art Contemporain in Nîmes, during Arles in 2018 – is a case in point. Through a rereading of colonialist discourses, the show was constituted not only by material objects but also images, archives, gestures and narratives.3

In photographic terms, we can think of archaeology not only as subject matter but as the driving impulse behind the excavation and activation of archive material – most pertinently here, in the form of collage and montage. Misdirection and misinformation go hand-in-hand with that process, resulting in images that urge the viewer to reconsider narratives they had constructed for themselves – around the types of photographs they already know. In other words, collage asks us to recalibrate our reference points. Heterogeneous, deconstructed, distorted, hybrid, fantasy – the nature of collage has made it a powerful tool. Particularly during times where historically manipulated truths are being scrutinised like never before. Together with its low economic means of production – the practice can take place equally in the studio, the bedroom, or simply on a laptop – a duality emerges between the political and the personal. By appropriating pre-existing imagery, photographic collage also variably involves questions around the consumption of information. The act of recycling itself carries with it an important message – to borrow is to say enough’s enough, let’s reinvent what already exists.

A curated compendium of recent photographic collage might look something like this: Ruth van Beek re-animates flower arrangement manuals from the 50s with The Arrangement, inspiriting her small-scale works with larger-than-life characters; Batia Suter compiles images of nature and the physical world with the voluminous Parallel Encyclopedia, exercising the iconification of images via playful and intuitive sequencing; Matt Lipps stages, lights and rephotographs cutouts from discontinued photographic handbooks with Library, creating disorientating spatial arrangements between appropriated images and stylised backdrops; Hannah Hughes reconfigures auction catalogues and journals with The Flatland Series, inverting overlooked negative spaces into sculptural constructions; Nico Krijno splices, scans and distorts found images with his Lockdown Collages, transposing ethnographic photographs of African tribespeople with ‘how-to’ books on ikebana and interior design. It’s no coincidence that most of these artists work with manuals; printed publications whose original function was instructional. By undermining that didacticism, they create alternative views of received histories. To borrow from Joan Fontcuberta, interventions such as these “challenge disciplines that claim authority to represent the real — botany, topology, any scientific discourse, the media, even religion.”4 A sentiment strongly shared by Giovanna Petrocchi, who, like Fontcuberta, incorporates fictional animals, reality-subverting techniques and irony into her work.

Originating from Rome, an outdoor museum in itself, Petrocchi describes the effect of that cultural fabric on her formative years. “Ancient sculptures, artefacts and archaeological sites are part of my cultural heritage and education – they have been impressed on my memory as a sort of mental imagery”, she says. Yet despite readily available access to such sites, Petrocchi’s work orientates more towards the impossibility of fully understanding and accessing the past. Playing with the practices of museum classification and categorisation in a way that highlights an inherent absurdity, Petrocchi’s arrangements of bones, relics and statuettes repeatedly resemble miniature theatre sets. Animated, juxtaposed and divorced from a rigid, linear reading, the characters in these sets are given license to roam free. In Modular Artefacts – a series parodying an imagined museum cataloguing procedure – we encounter monsters, mutant vessels, floating amulets and a conversation between a bird and an abstract shape. Like the source images that Petrocchi de-contextualises, her creatures too are fugitive; on the run. Not only that, they are intruders and disruptors – gate-crashing museum cabinets after the curators have gone home.

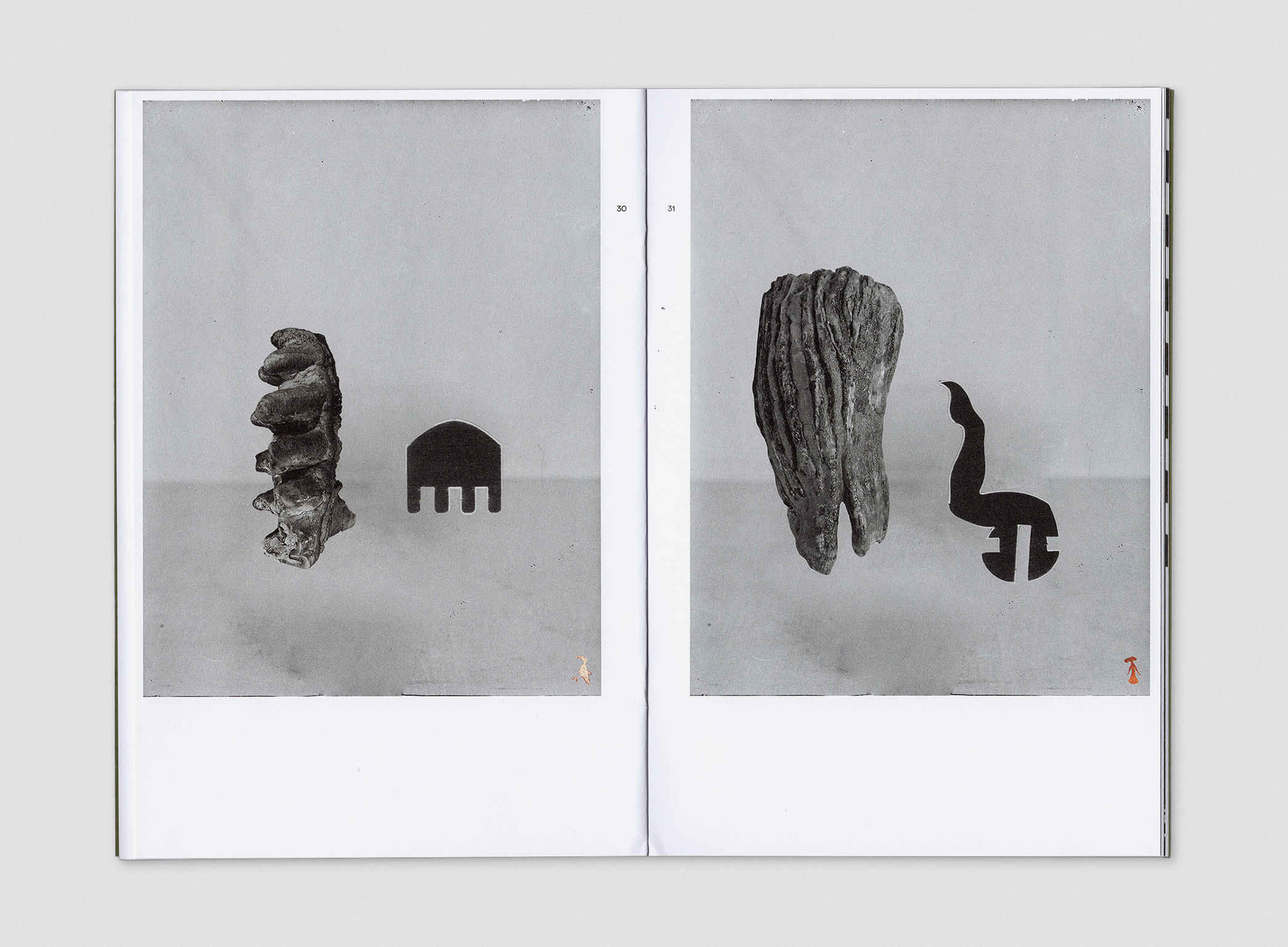

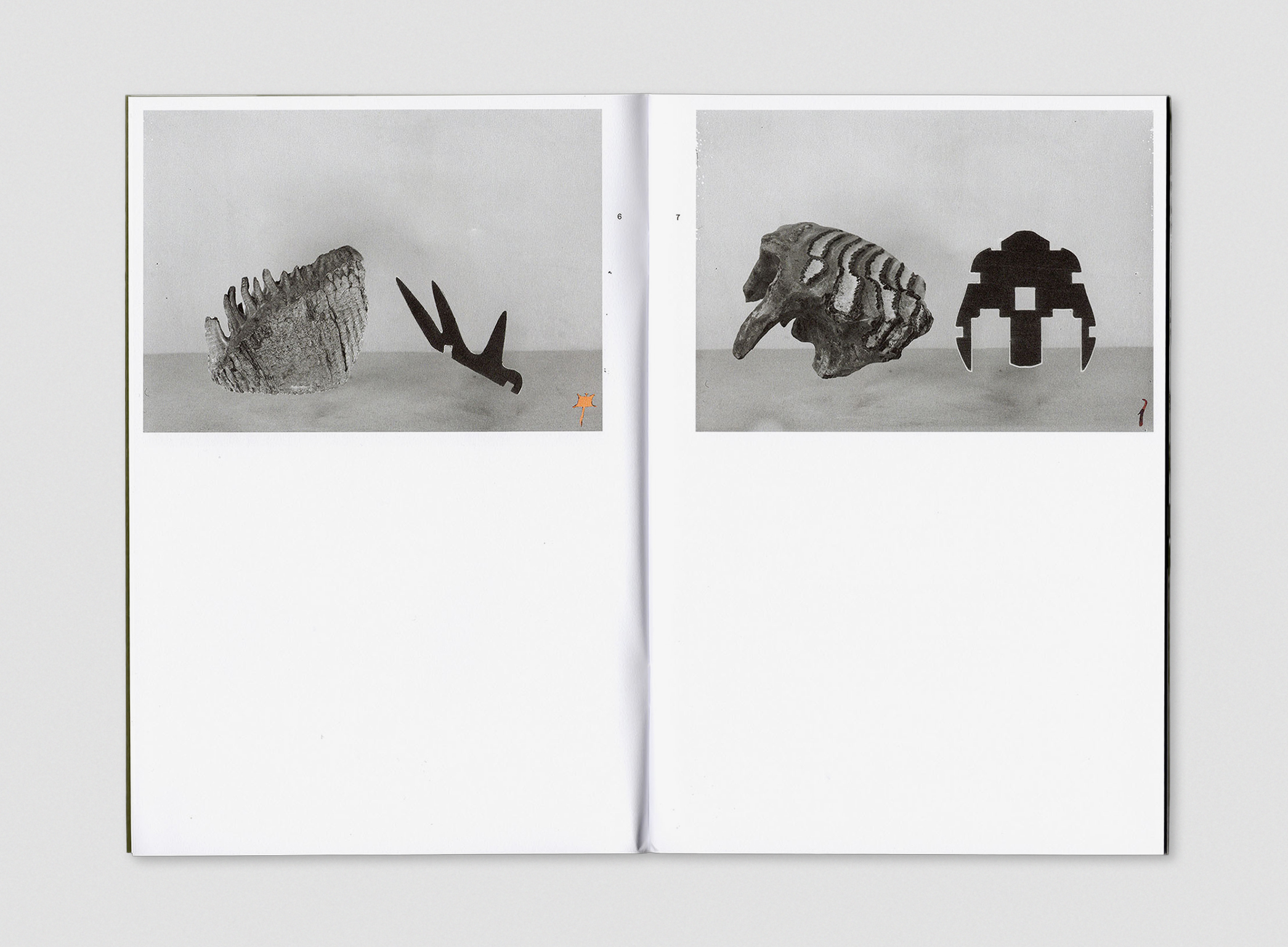

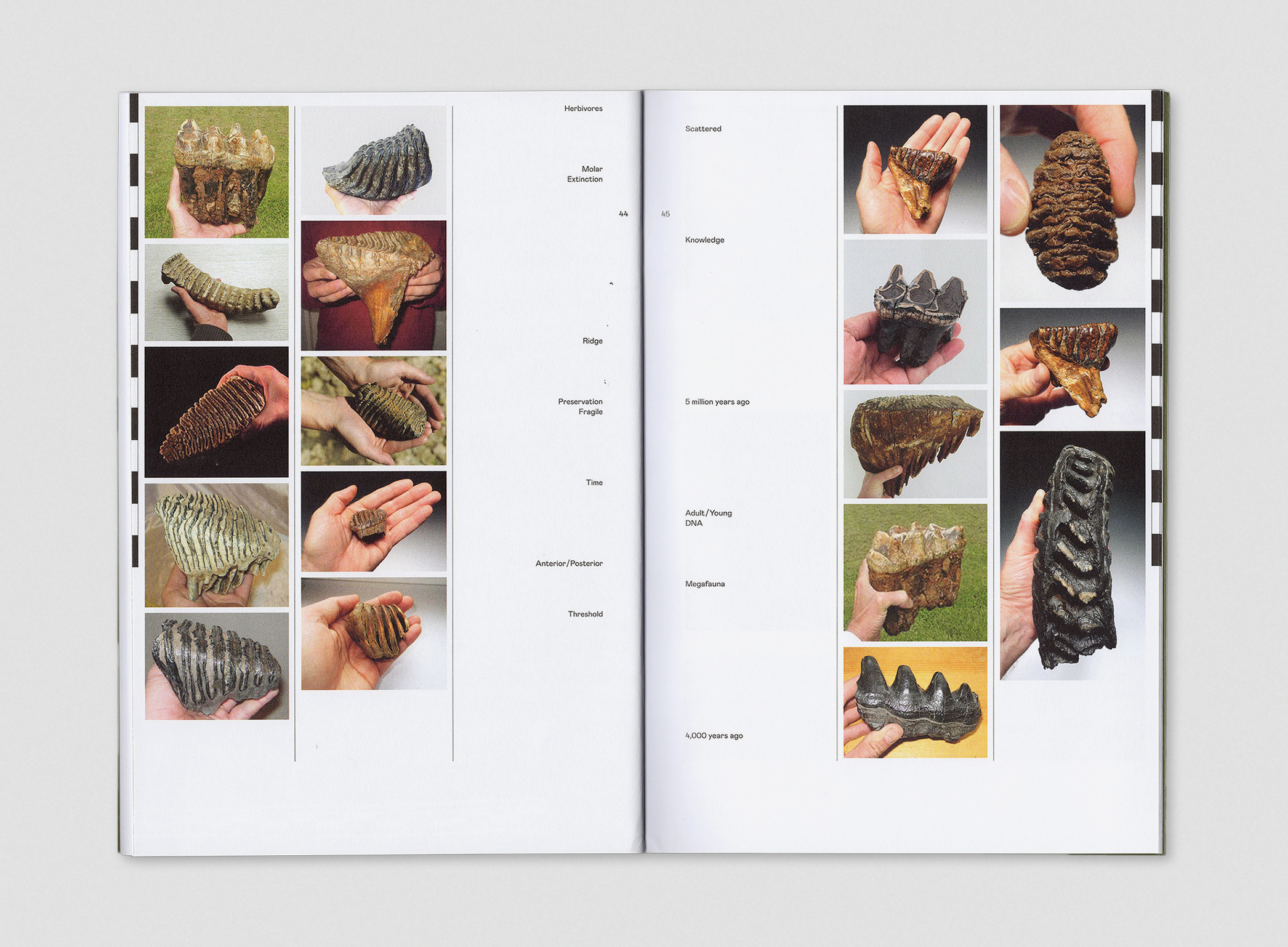

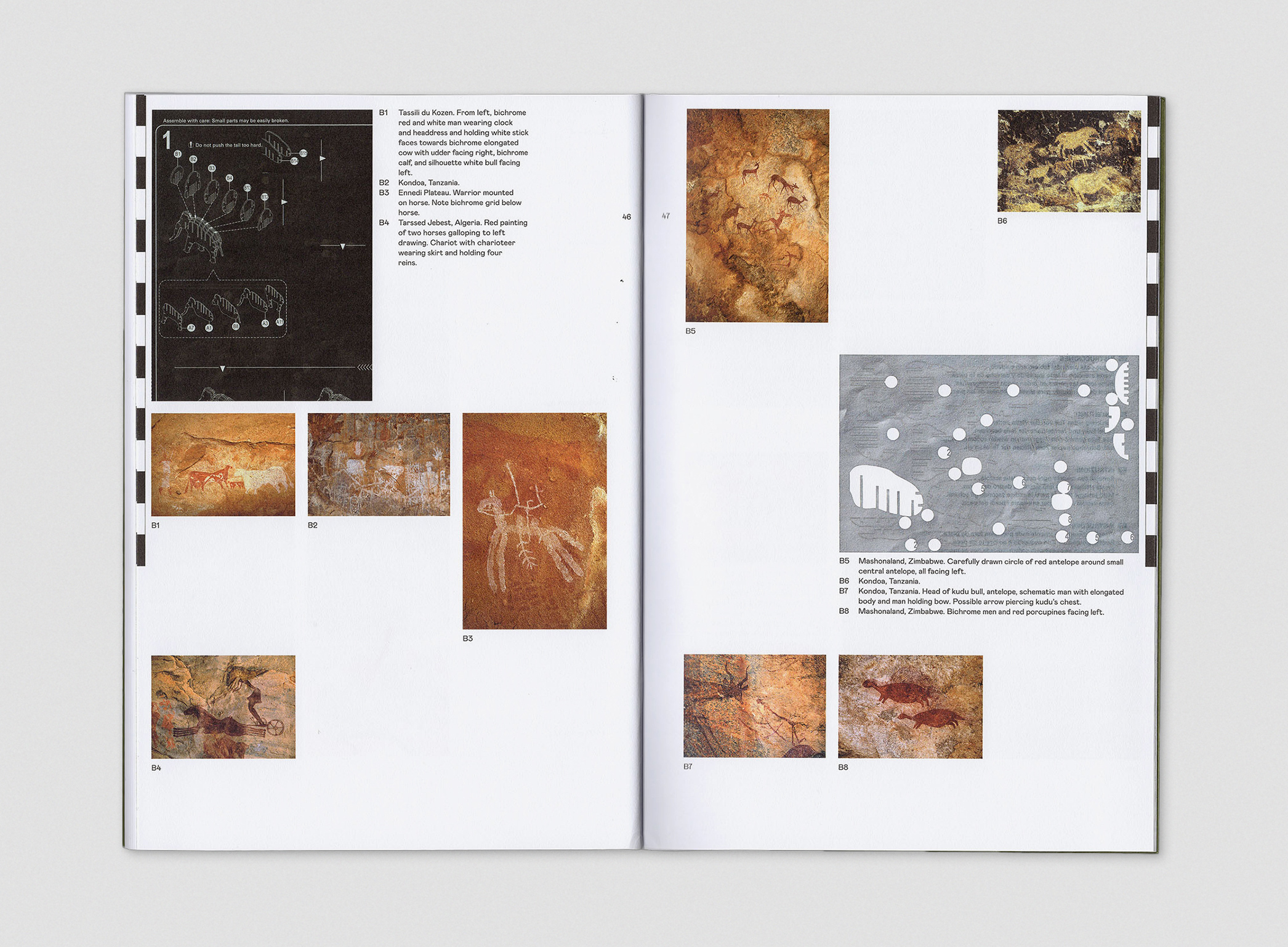

With Sculptural Entities, we see several of Petrocchi’s recurring visual themes coming together into a single framework that gets repeated. The ancient relic, represented here by the mammoth tooth fossils; the speculative contemporary form, embodied by the scanned cutouts from 3D dinosaur puzzle kits; the digital artefact, revealed in the overtly clone-stamped backdrops; and the mythological being, symbolised by the animal glyphs in each bottom right corner. Other, more subtle layers also emerge, such as the imperfections caused by damage to the original glass negatives – hinting at the analogue photograph as a relic in itself. Supplementing the main body of images, an ‘archive’ section purports to unpack layers of methodologies – as evidenced by measuring rulers, puzzle manuals and original in-tact images. Part ‘how-to’ guide, part postscript, these elements, whilst revealing, ultimately remain abstracted and illusive.

Layering and compression – qualities we can associate both with photography and stratigraphy (Earth’s geological and archaeological layers) become a lens through which to contemplate the work. Since 2009, The Anthropocene Working Group (an interdisciplinary research collective) have argued that the planet has shifted geologic time scale – from the Holocene epoch to the Anthropocene – where irreversible human impact is the agent of that change. Evidence for this partly comes from the material remnants of the technosphere (the technological systems of the Anthropocene), in other words, concrete, plastics and any synthesized materials. Compacted as layers within landfill sites or washed out to sea, these remnants are known as ‘technofossils’5. Potentially preservable for millennia, technofossil assemblages could conceivably become artefacts of the future. Petrocchi’s puzzle pieces, with their artificial structures counterpoised by the organic fossil samples, describe this paradigm. More than that, I would argue they are metonymic – themselves composed of wood, which has been machined and laminated.

Each of them unique, fossilised mammoth molars are naturally conserved under permafrost. At 1.2 million years old, DNA from a recent mammoth discovery was identified as the oldest known to science. In contrast, the puzzle pieces are computer-automated designs, produced by the batch-load in a matter of minutes. Both objects are anatomical, both are deconstructed in some form, though they couldn’t be further apart in timespan or scarcity. Yet in Petrocchi’s world, they are digitally composited into typological surfaces through printed internet sources. With their inherent flatness and uniformity – where everything can be reduced using standardised tools – digital technologies are particularly effective at comparing disparate entities. Through the visual trope of imitation, one possible reading is that the puzzle pieces attempt to mimic the fossils, albeit in a simplified geometric manner. Despite the appearance of a museographic sequence, any attempt to draw solid conclusions from such comparative methods is ultimately arbitrary. Does that make Petrocchi a bad museologist? Or through qualities like empathy and humour, does it animate the discourse in a refreshingly relatable way?

Imitation and mimicry have a strong lineage in an art-historical context. But this type of reading – one that seeks to attribute mind to matter and relationships between objects – might find a more abiding foundation in the belief system of Animism. A system that does not distinguish between human and nature, where all things – alive or allegedly inanimate – are characterised as living beings. And where all living beings are interconnected. While Animism likely has roots in ancient mythology, it is a growing school of thought in today’s world – no doubt resulting partly from our increasingly distant connection from multi-species communities. Giovanna Petrocchi’s work, with its fragmented animal representations, not only points to that disconnection but envisions new species and new communities. Against the outdated ideologies of western museums, her work contests the objectification of nonhumans – offering a more interwoven perspective on nature and culture.6

1Yuval Noah Harari, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, Penguin Random House, 2011

2Interview with Mark Dion, Whitehot magazine of contemporary art, 2009 http://whitehotmagazine.com/articles/2009-‐interview-‐with-‐mark-‐ dion/1833

3Jean-Marc Prevost, Carré d’Art, 2018 https://www.carreartmusee.com/en/exhibitions/a-desire-for-archaeology-138

4Joan Fontcuberta: False Negatives, interview with Stuart Jeffries, The Guardian, 2014 https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/jul/08/joan-fontcuberta-stranger-than-fiction

5The technofossil record of humans, Jan Zalasiewicz, Mark Williams, Colin N. Waters, Antony D. Barnosky, Peter Haff https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264461538_The_technofossil_record_of_humans

6Mariana Reyes, Interwoven Voices of the Anthropocene: Multi-species Stories in the Contemporary Museum Space, 2020 https://activisthistory.com/2020/04/08/interwoven-voices-of-the-anthropocene-multispecies-stories-in-the-contemporary-museum-space

by Chris Littlewood

Published in Giovanna Petrocchi, Sculptural Entities

A Corner With Editions, 2021

Other text by Sunil Shah

Design by Sara Cristina Moser

Edited by Trine Stephensen

One evening in September 2018, Brazil’s Museu Nacional in Rio de Janeiro was eviscerated by fire. As Latin America’s largest museum, its collection included some 20 million scientifically and culturally invaluable artefacts. Among those were dinosaur skeletons, a Pompeian fresco and the skull of Luzia – the oldest known human from Latin America. Devastated, as many Brazilians were by such a loss to their cultural heritage, the artist Vik Muniz was compelled to respond. Working alongside the scientists who were recovering what little remained, Muniz offered his capabilities in an attempt to retrieve some form of lasting connection to that history. Known for his ambitious photographic works that recreate popular imagery through complex collages, he was well placed for such an undertaking. By salvaging ash from precise locations in the wreckage, Muniz recomposed images of selected artefacts with material from their own remnants. Museum of Ashes, the resulting project, is a series of imitations either in photographic or 3-D printed form. Capturing some essence of the originals, they also highlight how visual artists can provide alternative possibilities in the face of scientific limitations.

“Scholars tend to ask only those questions that they can reasonably expect to answer,” says Yuval Noah Harari, author of Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. In describing early Homo sapien foragers, Harari points to a period, what he calls the curtain of silence, for which we have no concrete cultural knowledge. Only “a few fossilised bones and a handful of stone tools that remain mute under the most intense scholarly inquisitions.” Present-day tools can generate specific data like the DNA sequence of a mammoth tusk. But convey nothing about the meanings behind our prehistoric ancestors’ material expressions, such as the anthropomorphic animal engravings found on mammoth tusks. Many assume that the Paleolithic people who left those engravings – or those who drew the cave art at Serra da Capivara – had inherently the same minds of people today. Yet despite well-informed speculation, will we ever know what was behind their thinking? As Harari surmises, “these long millennia may well have witnessed wars and revolutions, ecstatic religious movements, profound philosophical theories, incomparable artistic masterpieces […] But these are all mere guesses. The curtain of silence is so thick that we cannot even be sure such things occurred – let alone describe them in detail.”1

Imperialism and the colonial impulse to acquire, map and collect has led to miscellaneous collections of artefacts and curios. Often housed in Western museums – not infrequently at the detriment of more vulnerable cultural groups – they represent, for some, an overwhelming history of inequality and destructive political ideology. And despite museums attempting to make their collections more widely available via open access public domains, the dilemmas of museology continue to run deep. What then is the role of contemporary artistic expressions in such a context? According to the artist Mark Dion “The job of the artist is to go against the grain of dominant culture, to challenge perception and convention.” Importantly for him, without destroying what was there before. Speaking about a group of like-minded artists, he says, “rather than dynamite the museum, our idea is to make the museum a better place, or more representative, more responsive, more enlightened, more interesting.”2 Unlike the sciences, that means asking questions without expectations; it means presenting highly subjective visual languages that not only challenge empirical theories. But also imagine potential new worlds – encoded with signs and symbols for future generations to decipher. After all, it was the human imagination that created ancient artefacts in the first place. In that spirit, we can picture the artist, not as an isolated genius but a link in the chain of cultural expression.

Archaeology and fragmentation are leading principles for creative people today. Identified by design curator Li Edelkoort as a predominant theme among young designers, her exhibition concept Post-Fossil brings together what she calls contemporary archaic forms. Excavating and recomposing, these design disciplines are rooted in a desire to hybridise earth-bound matter with technological advancements. By developing new material research in this fashion, Edelkoort argues that this generation of makers is fueled by their world existing in a time of disarray. Consequently, they are shifting the emphasis from a materialistic mentality – to one conscious of ecology and overconsumption. “They propose ritualistic tools for a new kind of well-being,” Edelkoort says. Likewise, established ateliers incorporate notions of archaeology into large-scale built projects, fragmentation into their research. Within what could almost be a movement, this propensity is also prevalent across the visual arts. Fittingly titled A Desire for Archaeology, Perspectives on the Future – an exhibition at Musée d’Art Contemporain in Nîmes, during Arles in 2018 – is a case in point. Through a rereading of colonialist discourses, the show was constituted not only by material objects but also images, archives, gestures and narratives.3

In photographic terms, we can think of archaeology not only as subject matter but as the driving impulse behind the excavation and activation of archive material – most pertinently here, in the form of collage and montage. Misdirection and misinformation go hand-in-hand with that process, resulting in images that urge the viewer to reconsider narratives they had constructed for themselves – around the types of photographs they already know. In other words, collage asks us to recalibrate our reference points. Heterogeneous, deconstructed, distorted, hybrid, fantasy – the nature of collage has made it a powerful tool. Particularly during times where historically manipulated truths are being scrutinised like never before. Together with its low economic means of production – the practice can take place equally in the studio, the bedroom, or simply on a laptop – a duality emerges between the political and the personal. By appropriating pre-existing imagery, photographic collage also variably involves questions around the consumption of information. The act of recycling itself carries with it an important message – to borrow is to say enough’s enough, let’s reinvent what already exists.

A curated compendium of recent photographic collage might look something like this: Ruth van Beek re-animates flower arrangement manuals from the 50s with The Arrangement, inspiriting her small-scale works with larger-than-life characters; Batia Suter compiles images of nature and the physical world with the voluminous Parallel Encyclopedia, exercising the iconification of images via playful and intuitive sequencing; Matt Lipps stages, lights and rephotographs cutouts from discontinued photographic handbooks with Library, creating disorientating spatial arrangements between appropriated images and stylised backdrops; Hannah Hughes reconfigures auction catalogues and journals with The Flatland Series, inverting overlooked negative spaces into sculptural constructions; Nico Krijno splices, scans and distorts found images with his Lockdown Collages, transposing ethnographic photographs of African tribespeople with ‘how-to’ books on ikebana and interior design. It’s no coincidence that most of these artists work with manuals; printed publications whose original function was instructional. By undermining that didacticism, they create alternative views of received histories. To borrow from Joan Fontcuberta, interventions such as these “challenge disciplines that claim authority to represent the real — botany, topology, any scientific discourse, the media, even religion.”4 A sentiment strongly shared by Giovanna Petrocchi, who, like Fontcuberta, incorporates fictional animals, reality-subverting techniques and irony into her work.

Originating from Rome, an outdoor museum in itself, Petrocchi describes the effect of that cultural fabric on her formative years. “Ancient sculptures, artefacts and archaeological sites are part of my cultural heritage and education – they have been impressed on my memory as a sort of mental imagery”, she says. Yet despite readily available access to such sites, Petrocchi’s work orientates more towards the impossibility of fully understanding and accessing the past. Playing with the practices of museum classification and categorisation in a way that highlights an inherent absurdity, Petrocchi’s arrangements of bones, relics and statuettes repeatedly resemble miniature theatre sets. Animated, juxtaposed and divorced from a rigid, linear reading, the characters in these sets are given license to roam free. In Modular Artefacts – a series parodying an imagined museum cataloguing procedure – we encounter monsters, mutant vessels, floating amulets and a conversation between a bird and an abstract shape. Like the source images that Petrocchi de-contextualises, her creatures too are fugitive; on the run. Not only that, they are intruders and disruptors – gate-crashing museum cabinets after the curators have gone home.

With Sculptural Entities, we see several of Petrocchi’s recurring visual themes coming together into a single framework that gets repeated. The ancient relic, represented here by the mammoth tooth fossils; the speculative contemporary form, embodied by the scanned cutouts from 3D dinosaur puzzle kits; the digital artefact, revealed in the overtly clone-stamped backdrops; and the mythological being, symbolised by the animal glyphs in each bottom right corner. Other, more subtle layers also emerge, such as the imperfections caused by damage to the original glass negatives – hinting at the analogue photograph as a relic in itself. Supplementing the main body of images, an ‘archive’ section purports to unpack layers of methodologies – as evidenced by measuring rulers, puzzle manuals and original in-tact images. Part ‘how-to’ guide, part postscript, these elements, whilst revealing, ultimately remain abstracted and illusive.

Layering and compression – qualities we can associate both with photography and stratigraphy (Earth’s geological and archaeological layers) become a lens through which to contemplate the work. Since 2009, The Anthropocene Working Group (an interdisciplinary research collective) have argued that the planet has shifted geologic time scale – from the Holocene epoch to the Anthropocene – where irreversible human impact is the agent of that change. Evidence for this partly comes from the material remnants of the technosphere (the technological systems of the Anthropocene), in other words, concrete, plastics and any synthesized materials. Compacted as layers within landfill sites or washed out to sea, these remnants are known as ‘technofossils’5. Potentially preservable for millennia, technofossil assemblages could conceivably become artefacts of the future. Petrocchi’s puzzle pieces, with their artificial structures counterpoised by the organic fossil samples, describe this paradigm. More than that, I would argue they are metonymic – themselves composed of wood, which has been machined and laminated.

Each of them unique, fossilised mammoth molars are naturally conserved under permafrost. At 1.2 million years old, DNA from a recent mammoth discovery was identified as the oldest known to science. In contrast, the puzzle pieces are computer-automated designs, produced by the batch-load in a matter of minutes. Both objects are anatomical, both are deconstructed in some form, though they couldn’t be further apart in timespan or scarcity. Yet in Petrocchi’s world, they are digitally composited into typological surfaces through printed internet sources. With their inherent flatness and uniformity – where everything can be reduced using standardised tools – digital technologies are particularly effective at comparing disparate entities. Through the visual trope of imitation, one possible reading is that the puzzle pieces attempt to mimic the fossils, albeit in a simplified geometric manner. Despite the appearance of a museographic sequence, any attempt to draw solid conclusions from such comparative methods is ultimately arbitrary. Does that make Petrocchi a bad museologist? Or through qualities like empathy and humour, does it animate the discourse in a refreshingly relatable way?

Imitation and mimicry have a strong lineage in an art-historical context. But this type of reading – one that seeks to attribute mind to matter and relationships between objects – might find a more abiding foundation in the belief system of Animism. A system that does not distinguish between human and nature, where all things – alive or allegedly inanimate – are characterised as living beings. And where all living beings are interconnected. While Animism likely has roots in ancient mythology, it is a growing school of thought in today’s world – no doubt resulting partly from our increasingly distant connection from multi-species communities. Giovanna Petrocchi’s work, with its fragmented animal representations, not only points to that disconnection but envisions new species and new communities. Against the outdated ideologies of western museums, her work contests the objectification of nonhumans – offering a more interwoven perspective on nature and culture.6

1Yuval Noah Harari, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, Penguin Random House, 2011

2Interview with Mark Dion, Whitehot magazine of contemporary art, 2009 http://whitehotmagazine.com/articles/2009-‐interview-‐with-‐mark-‐ dion/1833

3Jean-Marc Prevost, Carré d’Art, 2018 https://www.carreartmusee.com/en/exhibitions/a-desire-for-archaeology-138

4Joan Fontcuberta: False Negatives, interview with Stuart Jeffries, The Guardian, 2014 https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/jul/08/joan-fontcuberta-stranger-than-fiction

5The technofossil record of humans, Jan Zalasiewicz, Mark Williams, Colin N. Waters, Antony D. Barnosky, Peter Haff https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264461538_The_technofossil_record_of_humans

6Mariana Reyes, Interwoven Voices of the Anthropocene: Multi-species Stories in the Contemporary Museum Space, 2020 https://activisthistory.com/2020/04/08/interwoven-voices-of-the-anthropocene-multispecies-stories-in-the-contemporary-museum-space